I first discovered the Passamaquoddy about a decade ago when I was invited on a kayak trip by a friend who runs a Sea Kayak touring company. The trip was a revelation for me. We set out from St. Andrews, New Brunswick, and I was impressed by the twenty-eight foot tide and the lack of lobster buoys, since the lobster fishery in Canadian waters is a winter fishery. This also meant that there was a significant lack of commercial vessel traffic. We were only a forty-minute drive from Calais, Maine, but it felt more like a thousand. As one drives from St. Stephen to St. Andrews, there is a very noticeable shift in the geology from granite ledges and fir trees, to red sandstone and cedars. Paddling past sandstone arches sculpted by the tides and beaches of pink sand in a northern climate is a very different experience from the barren beauty of the granite ledges of the Maine coast.

The trip included seven clients and two guides, and I went as a guest of the guiding company. Mine was the only skin boat, certainly the only bairdarka in the group. I think that at first my skin boat, handmade paddle, and paddle jacket drew a certain skepticism, but as the trip played itself out I won many converts for the baidarka. The weather was good, the company engaging, and the food was excellent. Sitting around a campfire on the beach each evening and discussing the geography, the history, and the marine environment, was a true education and the beginning of a love affair with the region.

A chain of islands crosses the mouth of the bay and separates it from the rest of the Bay of Fundy. This gives the whole Passamaquoddy a feeling of protection that is misleading. While the island chain does protect the inner bay from the swells of the Bay of Fundy, the entire tidal contents of the bay must flow out and in around these islands twice a day creating extraordinarily dangerous currents, standing waves, and whirlpools. Another factor of these strong currents is that they stir up the small marine life in the water making a fantastic feeding ground for finback whales, minke whales and occasionally the rare right whale. There are strict protocols concerning approaching these animals no closer than 100 meters, however, no one told the whales. On one occasion, I was a part of a group of paddlers just drifting along, minding our own business, when a pod of curious whales surfaced all around us. This is not only a very rare experience but also a potentially dangerous one. It left all of us both awestruck and feeling very small.

Over the years, I have been drawn back to this area again, and again, because of its great beauty, the abundance of marine mammals and coastal birds. It is a spectacular area for kayakers to explore with a guide or as part of a guided trip, but, and I cannot emphasize this enough; these are very dangerous waters. Even expert paddlers who guide in other parts of the world would be wise to get a local guide with experience. Seascape Kayak Tours has been doing this longer than anyone else has in the area and has won a number of awards for the quality of what they do, check in with them, in my opinion they are the best.

Another part of the attraction of this area is the many creative and inspirational people I have met over the years, like Harry and Martha Bryan. Harry and Martha moved to the area to homestead in the 1970s. Harry is a boat builder and Martha works in canvas, they do beautiful work, and that alone is enough reason to visit, but they are also an inspiration to those of us that think we should leave less of a footprint in passing through this world. Harry’s inventions, his bio-diesel sawmill, band saw, and peddle-powered tools, are as neat in their own way, as his boats. The Bryans are just one example, another is a wonderful and funky inn in St. Andrews called Salty Towers. Part B&B, part Inn, part art gallery, it is also a bit of a local hangout for musicians and artists. Jamie Steel, who runs Salty Towers, is one of the prime movers of the St. Andrews Paddlefest, held each May. Paddlefest started in the early 90s as an Earth Day celebration and beach clean up, and was the brainchild of Bruce Smith, of Seascape Kayak Tours. What was once as a one-day event for local sea kayakers has evolved into a weekend event that combines sea kayaking, beach clean ups, and live music in several venues.

I wanted to share my reflections on this beautiful place because it has been a source if inspiration for me as an artist and outdoorsman, and because this truly unique area is currently threatened by a scheme to build a Liquid Natural Gas Terminal on the U.S. side of the bay. The project would involve building a pipeline across Northern Maine and introduce regular traffic of LNG tankers into the bay. There has been a lot of heated debate about whether bringing LNG to the area would be a good thing or a bad thing. As near as I can see, it would be a good thing for those people who stand to make fortunes off the lack of sound energy policy in the U.S., and a bad thing for the rest of us. I only bring this up (politics is not one of the themes of this site) because any readers who have found my description of the area interesting might want to check it out sooner, rather than later…there may not be a later.

You can find out more about this subject at https://www.savepassamaquoddybay.org/

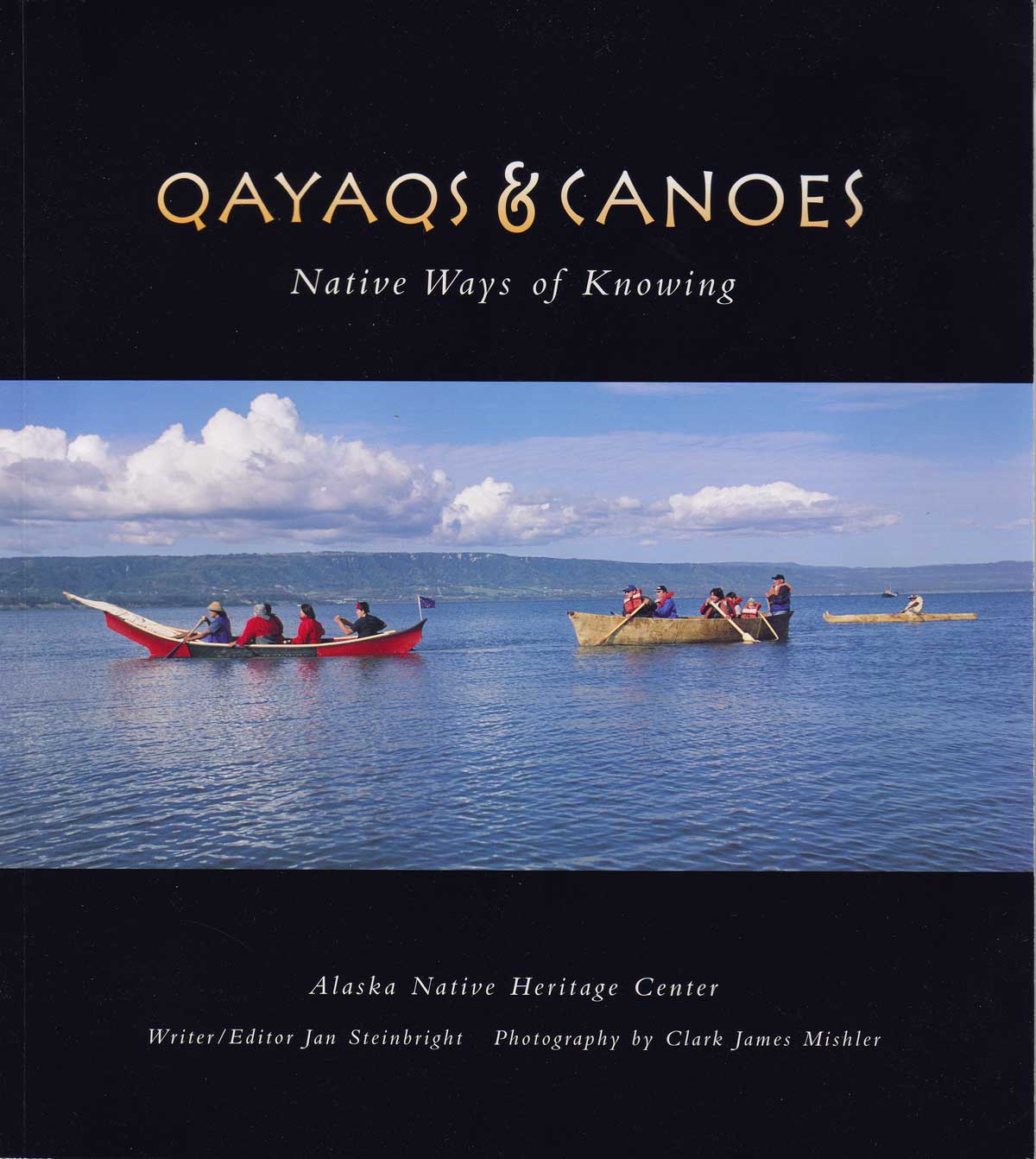

Some good friends from Alaska recently sent me a great addition to my library. A book and video tape called

Some good friends from Alaska recently sent me a great addition to my library. A book and video tape called