I have not written about wooden toys in a while and have not written about chess or other games in a really long time so I thought I would write about some of the games that live at the Wheelhouse.

First, another chess set. My brother found a cool ceramics place out in New Mexico where he lives, where you can come into the shop and can pick out ceramic pieces that are already bisque fired; paint them with supplies provided by the shop. The shop then fires your pieces for you and gives you a call when they are ready. My brother saw these chess pieces and thought it would make a great project. He painted the chess pieces and went home and made a neat chess board/table that he gave to me for the Celtic Wheelhouse. He went further, put a backgammon board on the reverse side of the board/table, and made the interior into storage space for the pieces. It is such a great gift and a clever project.

Next, is a Viking game I picked up many years ago in York while on a trip to England and Scotland. The game is a modern version, the pieces made of plastic, based on actual wood and or ivory pieces excavated at York. The game was popular in medieval Europe before chess was widely known. Sometimes called Hnefatafl, it is becoming popular again. The only problem with the game is that the box it came in fell apart and I was afraid of losing the pieces. My solution was to make a cedar box that looked like it might have been a made by the original players of Hnefatafl.

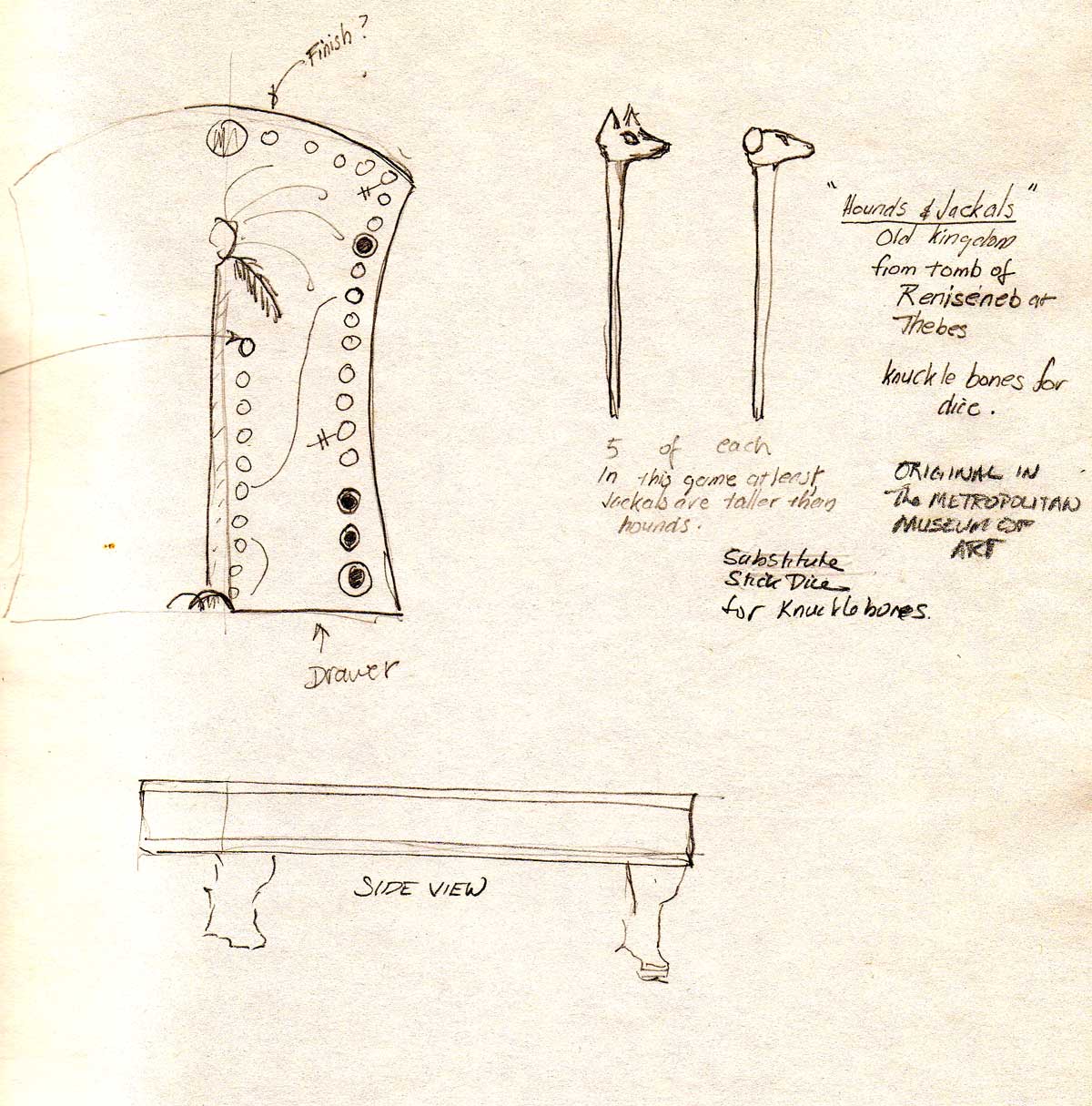

Hounds and Jackals is a game that was popular in ancient Egyptian times. I saw an original in the Metropolitan Museum in New York made of ivory. I made a sketch in the museum of the board, counted the number of pieces and holes, and then when I went home I made a version out of wood. I was teaching history of ancient civilizations at the time to ninth graders and when it was time to cover Egypt, I used to give them the copy of the game and ask them to look at it as an artifact. I was often amazed at how many correct deductions those ninth graders drew about the civilization that created the game based only what was in front of them. The other interesting observation I have, is that even though the game does not have any directions, kids in particular seem to have no difficulty figuring out how to play it. The only adaptation I have made is to substitute stick dice for the original knucklebone dice in the museum.

I should say that I am not much of a board game person myself, but I really love having these games out for visitors to play with, and get great pleasure out of watching others play with these various games from other periods in human history.